The Aesthetic Of Pollution

By Riet van der Linden

Once upon a time. billions and billions of years ago, a Big Bang took place. Planet Earth came into being as part of the Solar System. orbited by the Moon and nurtured with energy for life, by a large star. The Earth was round with a fluid heart of hellish fire which forced its way out, creating mountains and smoking craters. On Earth‘s surface the natural world came to life: oceans, lakes and rivers, continents covered with trees, plants and flowers, inhabited by insects, fish and reptiles and warm blooded mammals. And then, as a crown on creation, the human being came into existence.

In the beginning, animals and the first human beings lived together in peaceful harmony in what we call Paradise. But the humans, in their arrogance and disrespect, developed into dangerous predators, dominating and abusing each other and the natural world and all living beings in it.

“Where do we come from?" is an existential question, probably as old as humanity. The origin of our universe is, despite Darwin, part of a greater mystery. The many "creation myths" having become the source of most religions. But the subsequent question "Where are we gomg?" seems more urgent and relevant than ever. Overpopulation, over-consumption, environmental pollution, the extinction of animals and plants, and climate change, are part and parcel of the primacy of economic progress. Since the 1960s, scientists and environmental activists have tried to raise public awareness and get the attention of policymakers, but progress has been slow and not enough has been done to make a real shift. Most of us live in denial with respect to the disastrous consequences of our lifestyle, seeing them as a kind of inevitable, collateral damage. Most of us live in denial, rarely questioning how our ways of living bring about disastrous consequences for the planet. Many of us shrug and see it as natural, even inevitable. collateral damage.

As a young woman, like many of my generation, I became aware of environmental problems by reading The Limits to Growth, a report published In 1972 by the Club of Rome, which was founded in 1968 by European scientists. It was then that environmental issues entered the political agenda worldwide and is with us still. But clearly, economic growth is considered more important to a vast majority of people and governments than its consequences for the environment.

These days one cannot open a newspaper without being confronted with horror stories about major environmental disasters. An Iranian oil tanker, carrying 136,000 tons of crude oil, collides with a cargo ship off the coast of Shanghai and explodes. Shell and other big oil companies plan to drill for oil in the Arctic, the last great unprotected, safe haven for endangered species. According to The Guardian, reporting in collaboration with Global Witness, every week an average of four environmental activists are killed. In the meantime, wild animals are poached, tropical forests disappear rapidly, and bees worldwide mysteriously die. Marine pollution is another disaster. Common man-made pollutants that reach the ocean include pesticides, herbicides, chemical fertilizers, detergents, oils, plastic and other solids. According to scientists, micro plastic pollution in oceans is far worse than was initially feared.

Paradise Lost And Regained

Reflecting on the life and art or American artist Karen Hackenberg, I felt confronted not only anew with our environmental problems, but also with the question at what we, as artists, can do to effect change.

"What is it about human beings (...) that permits us to pursue activities that threaten our very survival?" wrote Suzi Gablik more than two decades ago, in her essay The Ecological Imperative. "What is it that is so important to us that we are apparently willing to destroy the planet - and ultimately ourselves — to get it? Why do we persist in these practices even after we realize their self-defeating futility?‘ Gablik's essay was published in Sculpting with the Environment, a provocative book in which the sculptor and educator Baile Oakes showcases the work at 35 internationally acclaimed environmental artists, all of whom believe that art can be a powerful social force with the power to change attitudes, values and—ultimately-behavior. Hackenberg is much more modest in this respect; she simply states that her art is like a raindrop falling on the surface at the ocean, but that many drops together can cause a wave.

I grew up by the seaside. I love nature and animals, and, like Karen Hackenberg, I am recycling and transforming waste into art. But, unlike Karen, I never presented mysell as an environmental activist and my art is not figurative and has no direct political purpose. Respect for all living beings and our natural environment, is a matter of fast to me. Recycling is and has always been my way of creating; my thoughts about meaning always come during the process or afterwards. I even feel irritated when curators or art lovers, in their search for meaning, react enthusiastically to the recycling aspect at my work in the first place and seem to have no eye for beauty, structure and form. Now I start thinking that maybe I am wrong, that my art too could be a drop on the surface of the ocean.

A good work of art is like a living organism. To make it “work”, every single part has to be inextricably bound up with form and meaning. This is exactly the quality I find in the Watershed paintings in which Karen Hackenberg, in an admirably intelligent and elegant way, deals with marine pollution and for which she was rewarded with prizes and public recognition.

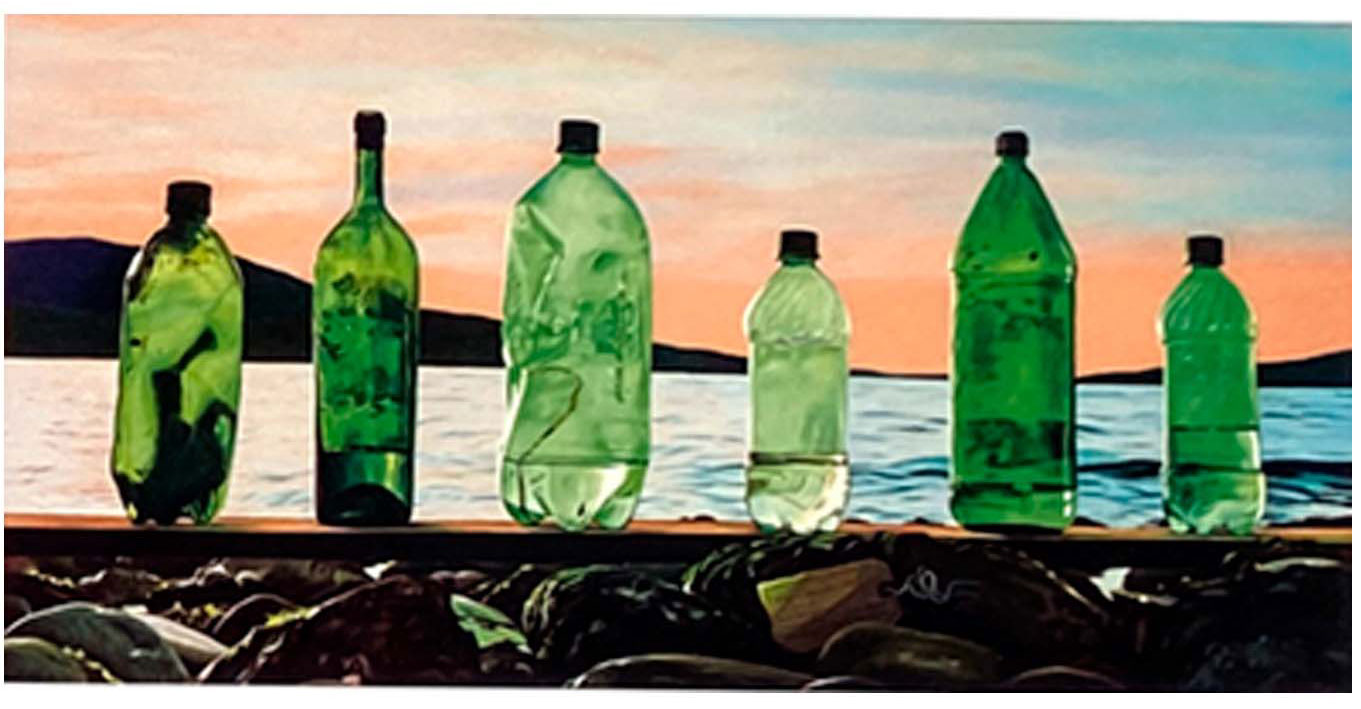

Hackenberg is an excellent craftswoman, painting with oil and gouache. Using this traditional technique, she handles the contemporary theme of marine pollution by juxtaposing a romantic Seascape (always Discovery Bay where she lives) with a still life of fiercely realistic, larger than life transparent plastic bottles and other, colorful plastic detritus. Her realistic Pop Art style, the monumental size of her paintings, the bullfrog perspective and the wordplay at the titles, often borrowed from the inscription on plastic packaging, are all elements forming a coherent and convincing unity.

Born in New Jersey and raised in rural Connecticut, Karon Hackenberg developed her first connections with the natural world on the shores of Long Island Sound. She studied painting at the Rhode Island School of Design in the mid 1970s and attended the Artists for Environment program for painting, with a focus on the appreciation and conservation of nature. After earning her BFA degree, the artist moved to the western US. She worked as, among other things, a designer at ecological textiles at the headquarters of Esprit in San Francisco. From there she moved to the Pacific Northwest, finally setting up her studio near Port Townsend, Discovery Bay, in Washington.

I can easily imagine Karen walking along the shores at “her” bay. I can hear the sound at the waves and smell the salty water of the ocean. And I know how this primeval landscape, dominated by nothing but an untamed sea under an enormous sky, can make one feel very insignificant yet also powerful. It is the same magic a surfer feels riding the waves. One only has to look at her paintings to realize that Karen Hackenberg is able to enjoy nature's beauty without closing her eyes to the polluting plastic trash. She even finds a way to distinguish a certain aesthetic in it. In her own words, ”I paint and craft artworks rising from a primal urge to simply create beauty by making things.”

Discovery Bay

It is my feeling that, it was on the shores of Discovery Bay that Karen Hackenberg found her own voice as an artist. Everything she learned, loved and experienced over the years came together there like a vision. For the first time she could express herself fully in her art in a way that made real sense to her, by communicating her lifelong love for nature in close connection with her concern for the environment. One can feel her pleasure in painting, her need to express beauty as a strategy for life and survival, as opposed to the ugliness of destruction and death. In her meticulous oil painting, the beautiful shores of Discovery Bay become the fixed décor of not only the incoming and outgoing tide, the blue sky over the water and the changing of the light, but also at plastic water bottles and other pollution which comes in on the tides.

Hackenberg is not an open-air painter. On location she carefully stages her compositions, which she then photographs “with her ear to the sand”, as a preparation for her paintings. In Shades of Green:Amphorae ca. 2012 Hackenberg almost lovingly reproduces and enlarges these bottles, focusing on their fogged transparency. From a ground-level perspective, these shiny bottles dominate the natural scene, like the grant stone statues on Easter Island, The ironic title Shades of Green:Amphorae ca. 2012 quite clearly refers to the abusive flirtation of commerce with the environmental awareness of the consumer.

"What is it that is so

important to us that we

are apparently willing to

destroy the planet - and

ultimately ourselves - to

get it? Why do we persist

in these practices even

after we realize their self-

defeating futility?"

suzi Gablik

-from her essay The Ecological Imperative

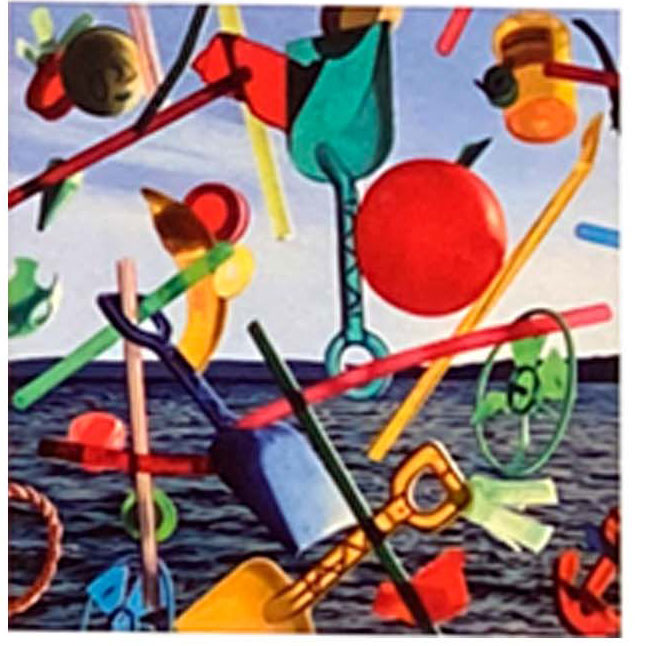

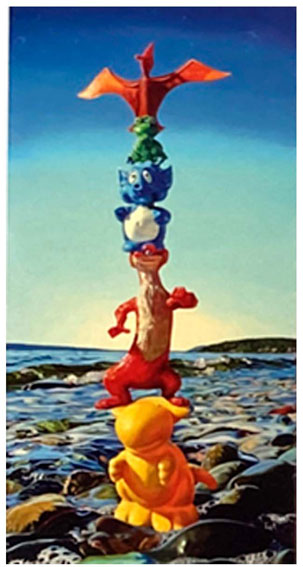

In her fascinating series The Floating World, Discovery Bay once again forms the décor for a colorful whirlpool or all sorts or small plastic objects and abstract shard,. floating in the atmosphere, seeming to swarm the way starlings do.

Most of us, when taking photographs of a scenic view, avold including cars, electrictty wires,or smoking factories on the horizon. In other words, we leave out everything that disturbs the ideal image. We manipulate reality by making it more beautiful than it is, In her Watershed series Karen Hackenberg does the reverse; what ls normally experienced as disturbing plays the leading part. One could say that there is a slightly perverse aspect to this kind at art, like softcore pornography used in advertisements, glossy and seductive. But Hackenberg, by creating an aesthetic of pollution is clearly not alraid of being subversive. She delivers her powerful message with consistent, high quality artistic force. The strength of her art lies in tho balance between medium and message and the ultimate unity of style, form and content, in which even the titles play a role. In that sense, Karen Hackenberg's paintings are no less than perfect images at an imperfect world.

Riet van der Linden, Karen Hackenberg.The Aesthetics Of Pollution, Dakota Art Editions, 2018